This past week we lost one of the greatest cartoonists of all time and a dear friend of ours, Sam Gross. Sam was 89 years old, leaving behind his incredible wife Isabelle and daughter Michelle. The Washington Post remarked his humor as “outrageous” and “cancel-worthy” which is a title I’m sure we will all hope to live up to. Sam drew nearly 30,000 cartoons in his lifetime, a number that’s hard to imagine—unless you’ve seen his studio (and his bathtub). There’s so many cartoons of his that could be called the perfect joke. I’ll put just four here, but know that there are, ahem, 29,996 more.

Without Sam there’s two giant bunny slippers left in the cartoon world, the likes of which no one could possibly fill. I asked my colleagues this week to share their memories of Sam. It’s hard to put into words what a huge influence he was in cartoons, but what follows is our best try.

-Hilary

One afternoon a bunch of New Yorker cartoonists were invited to have lunch with the film director, Gus Van Sant. The lunch was at the same place it had been for decades; the now-closed Pergola Des Artistes. As we noshed away on our duck salads, Sam held court as he often would, going into detail on the mechanics of a cartoon he’d done about Jesus using a big cross as a pole vault. I blurted out the idiotic remark, “Ha…Cross-fit.”

Sam paused, looked up at me, smirked, and enjoyed the groans that came from around the table. That smirk. That’s what I remember about Sam– he was always smirking at something silly if he wasn’t kvetching about pay rates for cartoonists.

He was always in our corner– never selfish about opportunities, always sharing information about pitching to other publications and sharing his knowledge about how to create a really good cartoon. Funny was the only metric. If it wasn’t funny, it didn’t work, no matter how noble or ‘clever’ the message of the cartoon. It had to be funny as all hell or it wasn’t worth the ink. So his 27,592 finished cartoons (he liked to remind us of the number) were the best ones, pruned from hundreds of thousands of potential other ideas.

I’ll really miss Sam. He was one of the best. I wrote a little more about him here.

_

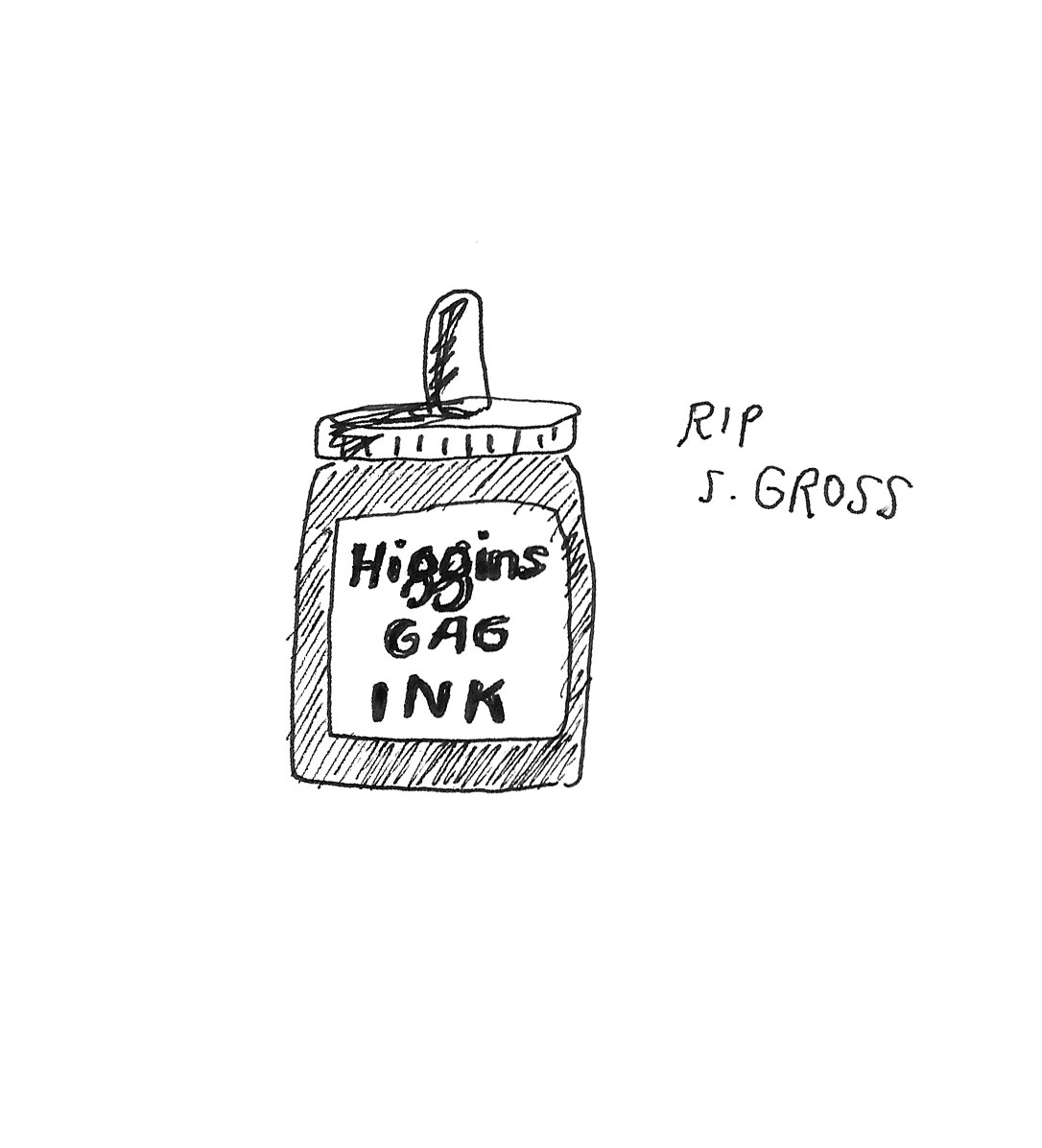

Sam Gross was a cartoon giant, even if he was a short man huddled over a drawing desk in the middle of Manhattan. The loss of his presence in our world is so deeply sad. He was one of the very first people I met when I started at The New Yorker, having weekly lunch with him, Sid Harris, George Booth, Mort Gerbeg and so many others at Pergola des Artiste will be one of the highlights of my life. One of my favorite jokes that he repeated to me nearly every time I saw him was that if anyone asks me what cartoonist tools are needed to be the best in the biz, I should reply “Higgins Gag Ink”--You can’t be funny without it! Of course Higgins Gag Ink does not exist. Higgins ink does, but it’s very entertaining to fuck with people.

Sam’s work made me feel so good because of how horribly dark it was. If he can make a living on Nazi cartoons, I can say the worst, most offensive joke that comes to mind, and we could laugh our asses off. We are so lucky to have had him on this earth, if you haven’t explored the thousands of S. Gross cartoons out there yet, I suggest you do so starting today. Might take you awhile.

_

Watching your hero decline in front of your very eyes is not for the faint of heart. But I went from very sad to feeling there is great cause for celebration. He accomplished so much and did so much for so many. I want to thank Sam for not staying an accountant. For giving us 70 years worth of cartoons to enjoy the rest of our lives. Thanks for being a part of our lives.

He started professionally as a cartoonist in the Army and I was wondering if it was there that Sam developed this sense of responsibility to watch each other’s back (as well as leaning into racy content from entertaining his classmates at the all-boys DeWitt Clinton High School and then troops of men when he went into the Army). If you were introduced to Sam as a cartoonist…or even if you just expressed your desire to become one, Sam had your back. You had earned his respect and became part of a special family. He was always the best cartoonist in any room, but in his eyes, everyone was equal. Everyone deserved to be heard. He was going to teach you to protect your work and your efforts. He was going to invite you to lunch even if you never got into “the magazine.” You were going to go and you were going to pay $24 for a lunch you were still hungry afterwards because you were going to be sitting with Sam Gross and you knew you could learn something from him that was priceless.

From Sam’s sketchbook:

I’ve heard that every week, The New Yorker has about 1000 cartoons submitted for the 12-20 weekly slots. It’s a hard gig, and it would be easy for New Yorker cartoonists to be cold and competitive with each other but instead I’ve found incredible support. That didn’t come from nowhere, that’s a cultural thing, passed down. I was shown kindness when I first showed up, and so it was a no-brainer to show kindness to those who showed up after me. Sam was a cornerstone of that tradition (along with Mort and so many others). It’s a tradition which you certainly don’t find in every profession or every art community (some of which seem hell-bent on passing down trauma rather than support, or even acceptance.)

Sam was a HUGE part of that culture. When I first showed up at the New Yorker I was lousy at drawing. Sam didn’t care that I was green, that maybe I would never get published, and instead he immediately launched into one of the best business-school lessons of my life.

“NEVER sell your copyright. NEVER. When I was working for Hugh at Playboy he wanted to buy copyright but I knew he was a cheap bastard. So I told him he could pay me a little less for my cartoons, but I keep copyright. Now I have all my cartoons - I can sell them, I can make books, they still make me money - and some of my friends who worked for him for decades, what do they have? NOTHING.”

At a New Yorker potluck Christmas Party, leaning down double to hear Sam amidst the cacophony of the room, he grumped “Bring your own food? I remember when the New Yorker Christmas Party was at the fanciest hotels in town, open bar, with a 16 piece band.” I looked around the room, both happy and very unhappy to get this piece of historical information.

Sam, the person, often reminded me to run my art as a business and don’t take any shit. Sam, the artist, was a reminder that you can tap into the darker parts of your brain and being funny definitely doesn’t mean being appropriate. Thank you Sam.

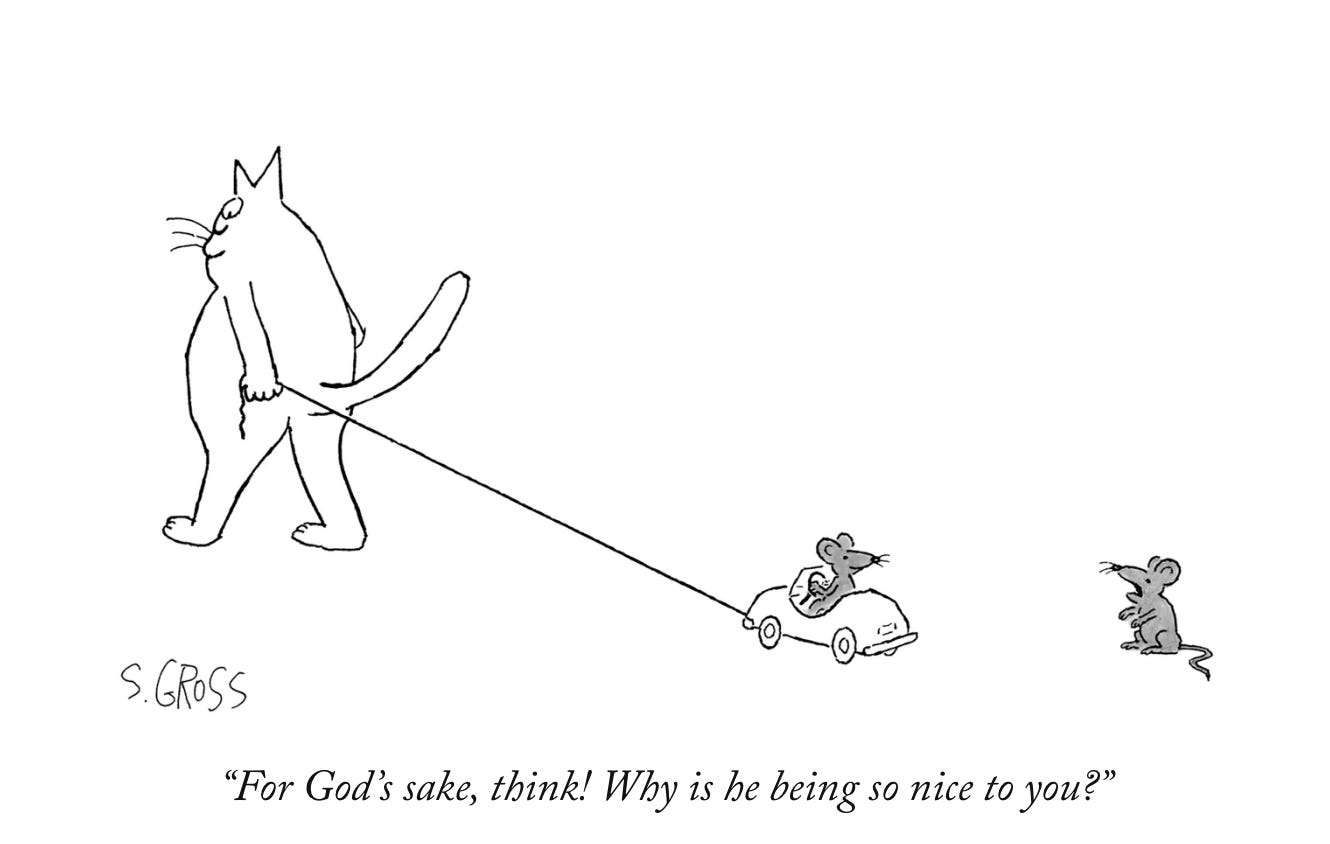

Sam, as we all know, has more and better gags than almost anybody - a product, I suppose, of his ruthless analytical mind, his drive, and his perverse sense of humor. Would that we were all so blessed. I have so many favorites of his, but I love this one in particular, in part because my husband and I say it to each other all the time. Like most of Sam’s work, it’s succinct, profane, and hilarious.

A few years back I was talking to Sam about one of the Conde Nast events I’d been hired to do - some kind of dog-and-pony show that they needed a pet cartoonist or two to show up for and draw little pictures for the attendees. “They don’t ask me to do those,” he rasped. And then, with amusement and not a little pride: “I don’t play well with others.” I do play well with others, and was immediately ashamed of that fact. Sam had more than talent and more than drive: he had balls. An absolutely enormous set of brass ones. I have no idea if Sam liked me or what he thought of my work. But I do know I was lucky to have known him, and to have him in my head and heart as an example to try my best to live up to - more love, more laughter, and much, much bigger balls.

For more about Sam’s prolific life in cartoons, read Emma Allen’s piece on him in The New Yorker from just a few days ago.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorite photos taken at what’s known as “The Bunny Bash” (hosted by cartoonist Bunny Hoest) back in 2017. Left to right: Jason Chatfield, Ellis Rosen, Sam Gross and of course, myself—Hilary.